If you don't have time to read this article but would like to know whether our software can help - it can. You can buy access to our software and get started immediately, 365 days-a-year.

Buy Preparation SoftwareMotor Skills describe the ability to coordinate muscular movement with sensory perception in order to perform physical tasks with precision, control and consistency. These skills are broadly categorised into two types known as Gross Motor Skills, which involve the larger muscles of the body and govern movements such as walking, running and lifting; and Fine Motor Skills, which involve the smaller muscles, particularly those of the hands and fingers, and govern movements requiring dexterity, accuracy and nuanced control.

In the context of pilot aptitude testing, it is predominantly Fine Motor Skills that are evaluated. The ability to make small, precise adjustments using the hands and fingers, often referred to as Hand-to-Eye Coordination, is a fundamental requirement of the professional pilot role and is one of the most heavily weighted competencies in candidate assessment.

Further Reading on Fine-Motor Skill and the Sensory-Cognitive-Motor Loop

Fine Motor Skill = Psychomotor Ability

In aviation psychology, Fine Motor Skill is formally known as Psychomotor Ability from Psycho-, meaning the mind's processing of sensory information, and Motor, meaning the physical movement that follows.

The term reflects the fact that these skills are not purely physical; they depend on the brain's ability to interpret what the eyes see and translate that information into precise physical action. You will encounter the term "psychomotor" frequently throughout pilot aptitude testing literature, and it refers to this same integrated process of seeing, processing and physically responding.

The Sensory-Cognitive-Motor Loop

This seeing-processing-responding loop, often described as the sensory-cognitive-motor loop, operates continuously and must function with minimal delay for effective performance. It is the same fundamental process at work whether you are threading a needle, playing a musical instrument, or flying an aircraft. What distinguishes high psychomotor ability is the speed, precision and consistency with which this loop operates, particularly under pressure.

The importance of psychomotor ability in aviation was recognised remarkably early. Research conducted in the 1920s identified motor coordination, alongside intelligence, perceptual speed and reaction time, as one of the major attributes required for a successful flying career [7]. Over a century later, psychomotor assessment remains a cornerstone of pilot selection worldwide, a testament to both its enduring relevance and its demonstrated predictive power.

Motor skills are exercised in virtually every physical activity undertaken in daily life, though they are often so habitual that their complexity goes unrecognised. The following are common examples of fine motor skills that closely relate to the psychomotor abilities assessed in pilot aptitude testing.

- Driving a vehicle:

- Maintaining lane position, adjusting steering input in response to road curvature, and coordinating acceleration and braking all require the same continuous sensory-motor feedback loop that underpins aircraft control. The driver processes visual information about road position, speed and traffic, then makes fine adjustments through the steering wheel and pedals.

- Playing a musical instrument:

- Instruments such as piano, guitar or drums require independent coordination of both hands, often performing different tasks simultaneously. This bilateral coordination is directly relevant to aviation, where a pilot may manipulate a side-stick with one hand and thrust levers with the other whilst operating rudder pedals with their feet.

- Handwriting and drawing:

- The ability to produce controlled, precise marks on paper relies on fine motor control of the fingers and wrist. Though seemingly distant from aviation, the underlying neurological processes (the conversion of visual intention into precise physical output) are closely related to those governing control input in the cockpit.

- Sports such as tennis, table tennis and badminton:

- Racquet sports demand rapid interpretation of a moving object's trajectory, prediction of its future position, and execution of a precise physical response within a narrow time window. This combination of visual tracking, prediction and motor execution is highly analogous to pursuit tracking tasks in pilot aptitude tests.

Further Reading on Video Games and Psychomotor Ability

The manipulation of a game controller or joystick to achieve precise on-screen outcomes is a direct analogue to the motor skills assessed in pilot aptitude tests. A growing body of evidence supports a meaningful link between video gaming and psychomotor ability.

What the Evidence Shows

Research published in 2024 found that high-level gamers demonstrated superior psychomotor speed compared to both low- and medium-skill participants, with higher levels of gaming proficiency linked to improvements in visuospatial memory, psychomotor speed and attention [10]. A separate study confirmed that regular video gaming correlates positively with psychomotor ability [11], while military selection research has found that both HOTAS (Hands On Throttle-And-Stick) experience and video gaming experience positively correlate with performance on psychomotor test batteries [9].

Recent research has also demonstrated that video game proficiency is a stronger predictor of simulated driving performance (including speed control and lane maintenance) than gaming experience alone [9], reinforcing the direct link between psychomotor skill and vehicle control. These findings are particularly relevant for candidates: engaging with joystick-based games can meaningfully support preparation for motor skills assessment.

The everyday examples above share a common thread - the coordination of visual input with precise physical movement.

In aviation, motor skills are exercised continuously throughout every phase of flight. The following examples illustrate how fine motor control and hand-eye coordination manifest in real flight operations:

- Manual flying and attitude maintenance:

- During manual flight, a pilot must make continuous small corrections to the aircraft's pitch, roll and yaw to maintain the desired flight path. These corrections are typically made through a control column, side-stick or yoke, and must be precise enough to maintain parameters within acceptable tolerances, often within a few degrees of bank or a few hundred feet of altitude.

- Crosswind landings:

- Landing in crosswind conditions requires the simultaneous coordination of aileron, rudder and elevator inputs to maintain the aircraft's alignment with the runway centreline whilst correcting for the lateral force of the wind. This demands a level of fine motor coordination that must be executed under time pressure and with significant consequences for error.

- Instrument approaches:

- Flying a precision approach such as an ILS requires the pilot to track both a localiser (lateral guidance) and a glideslope (vertical guidance) simultaneously, making continuous fine adjustments to maintain the aircraft on both reference paths. The tolerances are narrow and the workload is high, particularly in poor weather conditions.

- Engine failure management:

- In a multi-engine aircraft, the failure of one engine creates an asymmetric thrust condition that must be immediately corrected with rudder input whilst simultaneously managing the remaining engine's power output. The physical response must be both rapid and measured; too little rudder and the aircraft yaws dangerously; too much and control is equally compromised.

These demands are not exclusive to fixed-wing aircraft. Rotary-wing operations place equally significant, and in some respects greater, demands on a pilot's fine motor coordination:

- Hover maintenance:

- Helicopter pilots must coordinate cyclic, collective and anti-torque pedal inputs simultaneously to maintain a stable hover. This represents one of the most demanding motor skills tasks in all of aviation and requires constant, fine-grained physical input in response to changing aerodynamic conditions. The Micropat test battery, originally developed in the 1980s with the British Army Air Corps, was specifically validated against rotary-wing pilot training outcomes for this reason [3].

- Autorotation:

- In the event of an engine failure, a helicopter pilot must execute an autorotation — a rapid, precisely sequenced series of control inputs that converts the aircraft's altitude into controlled rotor energy. The collective must be lowered almost immediately, airspeed managed through cyclic input, and a flare timed within a narrow window before touchdown. The entire manoeuvre typically lasts under a minute and demands exceptional coordination under acute pressure.

- Low-level and confined-area operations:

- Operating a helicopter at low altitude, in confined spaces, or close to obstacles — as is routine in emergency medical services, search and rescue, and military operations — requires continuous, precise control inputs with minimal margin for overcorrection. The pilot must simultaneously manage the aircraft's position in three dimensions whilst accounting for wind, obstacles and changing visual references, often without the benefit of automated flight systems.

- Winching and underslung load operations:

- Maintaining a stable hover whilst a crew member is winched to or from the aircraft, or whilst carrying an underslung load, introduces constantly shifting weight and aerodynamic forces that the pilot must counteract in real time. The motor control required is both delicate and sustained, often for extended periods in challenging environmental conditions.

Motor skills are among the most consistently assessed competencies across all major pilot aptitude test batteries. The inclusion of psychomotor evaluation in pilot selection is supported by a substantial body of research spanning more than eighty years, and is driven by several key considerations.

Professional pilot training represents a significant financial investment, often exceeding £100,000 for an integrated ATPL course. A candidate who struggles with the psychomotor demands of manual flying is likely to require additional training hours, remedial instruction, or in worst-case scenarios may be unable to complete the course at all.

An FAA report reviewing 15 pilot test batteries and selection processes concluded that there is evidence of psychometric reliability and useful validity for the test batteries used in pilot selection, and that these assessments serve an important function in predicting the primary job performance criterion: success or failure in training [13]. Motor skills testing helps to mitigate the financial risk of training failure by identifying candidates whose baseline psychomotor aptitude is sufficient to meet the physical demands of the programme.

Whilst modern aircraft incorporate increasingly sophisticated automation, the ability to fly manually remains a critical safety requirement. Situations such as automation failure, unusual attitudes, wind shear encounters and go-arounds all demand immediate, precise manual control. Regulatory bodies such as EASA and the FAA recognise the importance of manual flying skills, and airlines accordingly place significant weight on psychomotor assessment during the selection process.

Multiple studies have confirmed that assessments measuring motor abilities are significant predictors not only of training success but of overall pilot performance [2] [4], lending support to the view that psychomotor aptitude has implications extending well beyond the training environment and into operational flying.

It is important to understand that motor skills testing evaluates aptitude (that is, the candidate's natural potential to develop psychomotor proficiency) rather than existing skill. A candidate is not expected to know how to fly an aircraft before sitting the assessment. Rather, the test seeks to measure the underlying neurological and physiological attributes that determine how readily a candidate will acquire these skills during training.

Research by Prokopczyk and Wochyński (2022) has argued that specialised psychomotor training should be provided to cadet pilots as part of their skill preparation, given the importance of habituation and automatisation of psychomotor skills in flying advanced aircraft [12]. This distinction between aptitude and skill is significant for candidates: preparation should focus on familiarisation with the test format and building confidence in the use of input devices, rather than attempting to learn entirely new motor abilities from scratch.

Further Reading on Predictive Validity and Historical Evidence

What is Predictive Validity?

When researchers evaluate whether an aptitude test actually works (that is, whether it genuinely identifies candidates who will go on to succeed) they measure something called predictive validity. This is expressed as a number between 0 and 1, known as a validity coefficient. A score of 0 would mean the test has no relationship with training success at all (it predicts nothing), whilst a score of 1 would mean the test is a perfect predictor (every candidate's score exactly matches their eventual outcome). In practice, no personnel selection test achieves a score of 1, as human performance is too complex for any single measure to predict perfectly. In the field of personnel selection, a validity coefficient above .20 is generally considered useful, above .30 is considered strong, and above .40 is considered very strong.

What the Research Found

Psychomotor aptitude testing is one of the strongest individual predictors of success in professional pilot training. In the most comprehensive meta-analysis of pilot selection research to date, Martinussen (1996) examined 66 independent samples from 50 studies and found that psychomotor and information-processing tests scored .24 on the predictive scale [1], comfortably above the .20 threshold considered useful, and a result that tells us these tests genuinely work.

To understand how significant that is, consider how psychomotor testing compares to the other types of assessment used in pilot selection. Martinussen found that psychomotor tests were just as effective at predicting training success as tests of cognitive ability such as maths and reasoning (also .24), and considerably more effective than personality questionnaires (.14), general intelligence tests (.16), or academic exam results (.15) [1]. In plain terms: how well you control a joystick tells selection teams more about your chances of becoming a pilot than your exam grades or your personality profile.

The Power of Combined Assessment

Perhaps the most striking finding was what happened when psychomotor and cognitive tests were used together. Individually, each scored .24. But when the two were combined into a single composite score, the predictive power jumped to .37, well into "strong" territory, and the highest score of any predictor category in the entire study [1]. The implication is straightforward: psychomotor testing captures something about a candidate that cognitive testing alone misses, and vice versa. Airlines and selection bodies that use both types of assessment in combination get a significantly more accurate picture of each candidate's potential than those relying on either one in isolation.

These findings have been independently replicated. A validation study of the U.S. Air Force's Pilot Candidate Selection Method (PCSM), which combines cognitive ability, aviation knowledge and psychomotor ability into a single composite score, found a corrected correlation of .53 with T-6 primary training completion [4]. To put that in practical terms: a composite score that includes psychomotor testing correctly distinguishes between candidates who will and will not complete training more than half the time, a level of accuracy that is exceptionally strong by the standards of any personnel selection process. Hunter and Burke's (1994) meta-analysis similarly confirmed that motor abilities were significant predictors of both flight training success and overall pilot performance [2].

The WWII Research Programme

The predictive power of psychomotor testing in pilot selection is not a recent discovery. During the Second World War, the U.S. Army Air Forces conducted what remains one of the largest and most rigorous pilot selection research programmes in history. Among its findings, an unrestricted sample of 1,152 men who underwent only medical screening (without any aptitude testing) was followed through all stages of flight training. The success rate was just 23% [6] [7], meaning more than three-quarters of candidates failed to complete training when no aptitude screening was applied.

80+ Years of Consistent Results

This wartime research identified the Complex Coordination test and the Two-Hand Coordination test, both psychomotor assessments originally developed by Mashburn in 1934, as significant predictors of training outcome. Remarkably, a comprehensive review by Griffin and Koonce (1996) found that automated, computerised versions of these same tests remain as predictive of military pilot performance today as they were over eighty years ago [3]. The Two-Hand Coordination test, in particular, bears a direct resemblance to the VTS Two-Hand Coordination (2HAND) module still employed in modern pilot selection.

The tracking tasks described later in this article, where a candidate uses a joystick or other input device to follow a path, maintain a position, or navigate through obstacles on screen, belong to the same fundamental category of assessment that has been used in pilot selection since the early 1940s. Despite enormous advances in technology, the core principle has remained unchanged: present the candidate with a dynamic visual challenge, measure how precisely they can respond with physical input, and use that measurement to predict how they will perform in the cockpit. According to the European Association for Aviation Psychology, this category of test has demonstrated continuous predictive success across more than eight decades of use [7].

Computerised pilot aptitude tests evaluate motor skills using tracking tasks: exercises where the candidate must control an on-screen element using a joystick, mouse or keyboard. Although different test systems present these tasks in very different ways (tunnels, flight instruments, abstract shapes), the research literature recognises two fundamental types of tracking task, each measuring a distinct aspect of psychomotor ability [3].

Compensatory tracking requires the candidate to keep an object in a fixed position despite external forces pushing it away. Typically, an element on screen will drift or move erratically, and the candidate must apply corrective input (through a joystick, mouse or keyboard) to push it back to the centre and hold it there.

Think of it like balancing a ball on a tray in a strong wind. The ball keeps trying to roll off, and your job is to constantly tilt the tray to keep it centred. You are not trying to move the ball anywhere; you are trying to stop it from moving. In flying, this is directly analogous to maintaining stable flight in turbulence: the aircraft is constantly being disturbed, and the pilot must make continuous small corrections to keep it where it should be.

Research into U.S. Navy pilot selection found that compensatory tracking tasks were significant predictors of success in naval flight training [3]. Compensatory tracking is the primary skill evaluated in the VTS Sensomotor Coordination (SMK) module, the COMPASS Control module, and the CBAT Sensory Motor Apparatus Test (SMA).

Pursuit tracking requires the candidate to follow, chase or acquire a target that moves or changes position. Rather than holding something still, the candidate must continuously guide their controlled element to where the target is, or where it is going.

Think of it like following a car ahead of you on a winding road. The road keeps changing direction, and you must constantly adjust your steering to stay on it. Unlike compensatory tracking where the goal is to maintain one position, pursuit tracking requires you to keep adjusting to a changing reference point. In flying, this simulates tasks such as tracking a localiser during an instrument approach, navigating through a series of waypoints, or maintaining formation position.

The Two-Hand Coordination test, a pursuit tracking task originally developed by Mashburn in 1934, was identified as a significant predictor of Air Force and Navy training outcomes, and computerised versions remain equally predictive today [3]. Pursuit tracking is the primary skill evaluated in the VTS Two-Hand Coordination (2HAND) module, the COMPASS Slalom module, the Aon Complex Control (wingChallenge), the CBAT Auditory Capacity Test (ACT), and the CBAT Rapid Tracking Test (RTT).

Whilst compensatory tracking and pursuit tracking are the two fundamental types of psychomotor task used in pilot selection, different test systems present them in very different ways. Understanding the presentation format of a module can help candidates know what to expect, even though the underlying skill being measured is the same.

Abstract Format

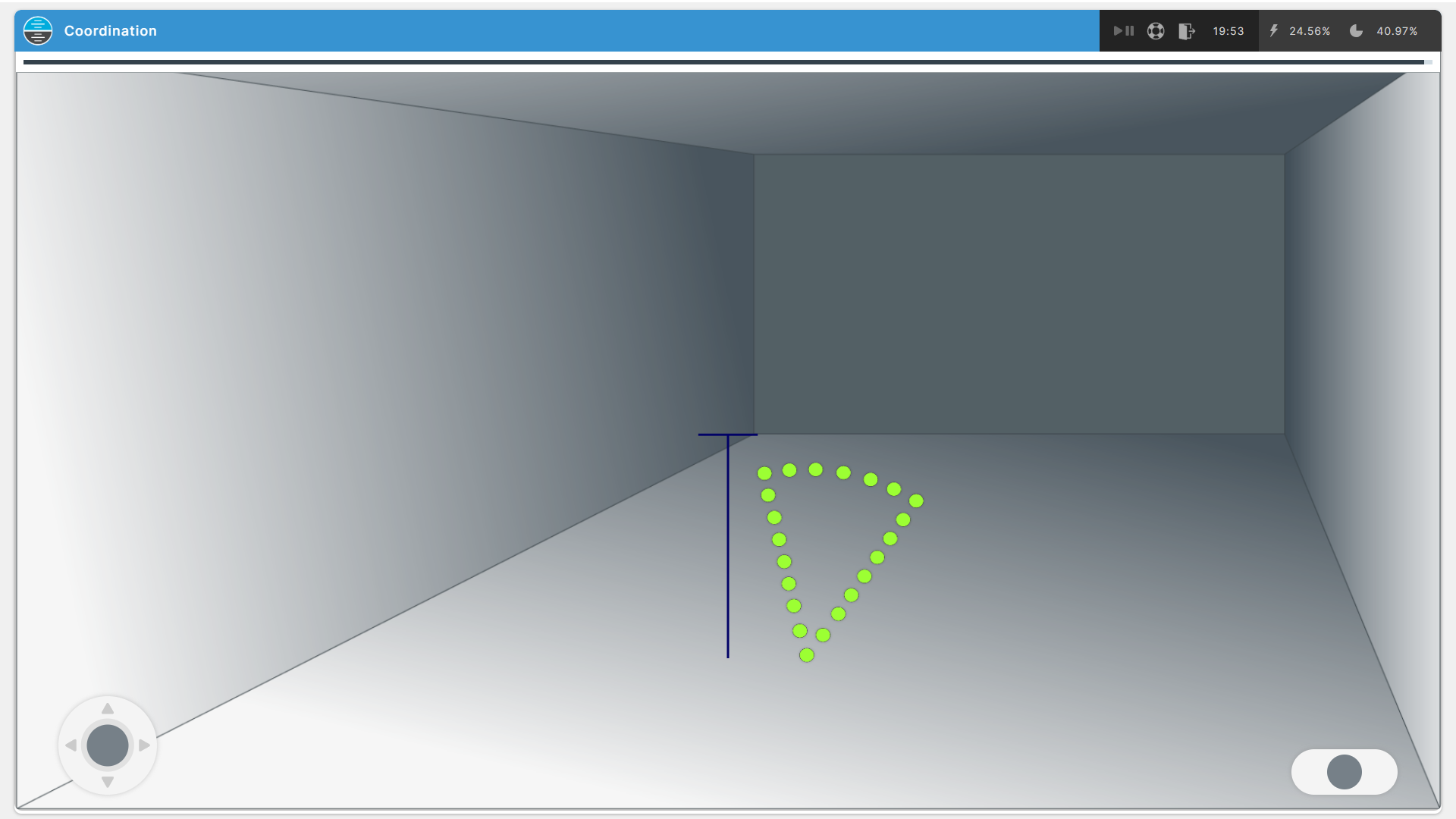

The simplest presentation. The candidate interacts with geometric shapes (circles, balls, crosshairs) on a plain background with no attempt to simulate a real-world environment. The VTS SMK, COMPASS Control, and CBAT SMA modules all use this format. It isolates pure psychomotor ability with minimal additional cognitive load.

Path-Following and Navigation Format

The candidate guides an element along a defined route or through a series of gates. The VTS 2HAND module uses a randomly-generated path, whilst the COMPASS Slalom presents the route as a series of gates that an aircraft must fly through. The underlying pursuit tracking demand is the same; the visual presentation provides a more intuitive spatial context.

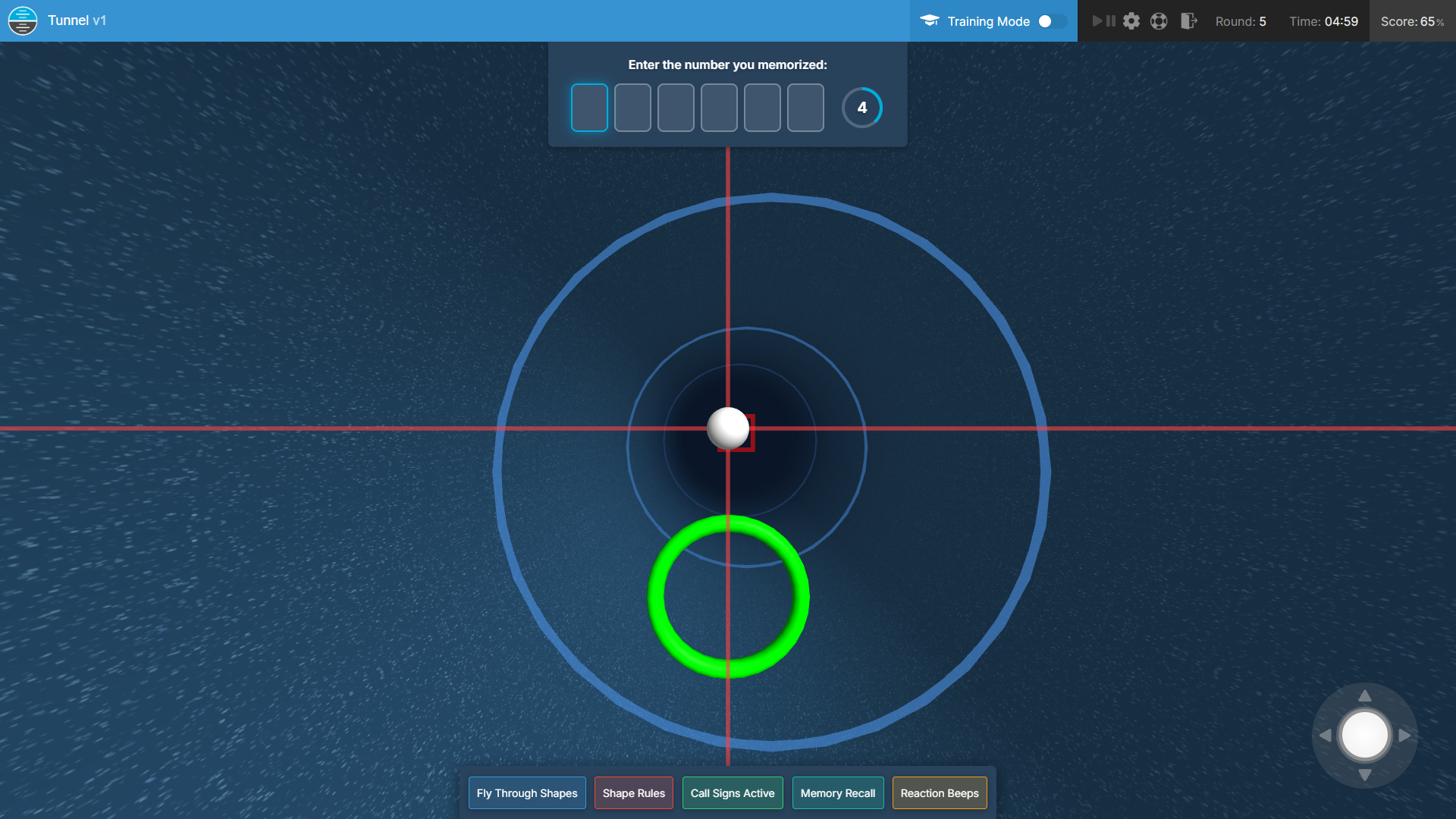

Tunnel Format

The candidate navigates through a three-dimensional tunnel that narrows and rotates, avoiding obstacles. The Aon wingChallenge and CBAT ACT modules use this format. Although the visual presentation is more immersive, the core task remains pursuit tracking: guiding a controlled element along a continuously changing path.

Target Acquisition Format

Rather than following a continuous path, the candidate must rapidly reposition their controlled element to acquire a series of discrete targets. The CBAT Rapid Tracking Test (RTT) uses this format. It is a speed-emphasised variant of pursuit tracking that places particular emphasis on reaction time alongside precision.

Instrument Format

The most realistic presentation. The candidate reads simulated flight instruments, such as a Primary Flight Display (PFD), and makes physical inputs to achieve and maintain the parameters shown. The Advanced COMPASS Complex Control Task and DLR Instruments (MIC) modules use this format. These modules typically blend both compensatory and pursuit tracking demands, because maintaining target parameters on an instrument requires both correcting for disturbance and following changing reference values.

Further Reading on Input Devices used in Testing

What input devices are used in testing of pilots?

The physical input devices used in motor skills assessment vary by test system:

The Vienna Test System employs a joystick, foot pedals and a proprietary input device similar to a keyboard in construction and augmented with a small joystick or ball-rotating trackpad.

Similarly, the COMPASS, Advanced COMPASS and CBAT test batteries use a joystick and rudder pedals in coordination with a keyboard.The DLR assessment uses specialist hardware at dedicated testing centres in Hamburg and Zurich and, given the relative simplicity of the test battery, Aon assessments are completed using a standard keyboard or mouse, though the motor control demands remain significant.

Given that military research has demonstrated a positive correlation between HOTAS experience and psychomotor battery performance [9], we recommend using a USB Joystick when preparing with our software for activities which simulate joystick-based assessments.

Whilst each pilot aptitude assessment relies on the same underlying principles to evaluate motor skills, the names and formats of the individual modules differ between test systems.

Effective preparation begins with identifying your assessment, understanding which modules evaluate motor skills, and then engaging with targeted practice activities.

Motor skills are assessed across a wide range of computerised pilot aptitude tests employed by airlines, flying schools and military selection programmes worldwide.

Select an assessment above to view its dedicated Knowledgebase Article for a full breakdown of all modules, not just those evaluating motor skills.

Once you know which assessment you will be undertaking, use the table below to identify the specific modules within that assessment that evaluate motor skills.

Each module targets a particular aspect of psychomotor ability, presented in a different format. The final column indicates which activity within our software corresponds to each module.

| Assessment | Module | Tracking Type | Presentation | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aon (Cut-e) | Complex Control (wingChallenge) | Pursuit | Tunnel Format | Spin |

| COMPASS | Control | Compensatory | Abstract Format | Control |

| COMPASS | Slalom | Pursuit | Navigation Format | Slalom |

| Adv. COMPASS | Complex Control Task | Compensatory + Pursuit | Instrument Format | PFD |

| CBAT / CFAST / FAT / MACTS | Auditory Capacity Test (ACT) | Pursuit | Tunnel Format | Tunnel |

| CBAT / CFAST / FAT / MACTS | Rapid Tracking Test (RTT) | Pursuit | Target Acquisition Format | Scout |

| CBAT / CFAST / MACTS | Sensory Motor Apparatus Test (SMA) | Compensatory | Abstract Format | Motor Control |

| Vienna Test System | Sensomotor Coordination (SMK) | Compensatory | Abstract Format | Coordination |

| Vienna Test System | Two-Hand Coordination (2HAND) | Pursuit | Path-following Format | Path |

| DLR | Instruments (MIC) | Compensatory + Pursuit | Instrument Format | Simulate |

Having identified the modules relevant to your assessment, you can navigate directly to the corresponding activities within our software.

Our software organises activities by the type of assessment you are preparing for, the skill being evaluated, and the specific airline, flying school or cadet scheme you are applying to. This means you do not need to manually cross-reference the table above - the relevant motor skills activities will already be included in your tailored preparation.

To find the activities relevant to you, navigate to one of the following within the software:

- Activities by Aptitude Test

- If you know which test system your assessment uses. For example, to find motor skills activities for Aon (Cut-E), navigate to Activities by Aptitude Test and select Aon (Cut-E).

- Activities by Skill

- If you want to focus specifically on motor skills across all test systems. Navigate to Activities by Skill and select Motor Skills to see every relevant activity.

- Activities by Airline, Flying School or Cadet Scheme

- If you know where you are applying but not which test system is used. For example, to find all activities relevant to Emirates - including motor skills - navigate to Activities by Airline and select Emirates.The software will include the appropriate motor skills activities alongside all other relevant preparation.

If you have created a Preparation Strategy, the relevant motor skills activities will already appear in your Focus Activities — no additional navigation is required.

Motor skills are closely associated with several other competencies assessed in pilot aptitude testing. Candidates preparing for motor skills modules may also benefit from developing the following related skills:

Academic Sources referenced in this KB Article

The following academic sources were consulted in the preparation of this article:

[1] Martinussen, M. (1996). Psychological measures as predictors of pilot performance: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Aviation Psychology, 6(1), 1–20.

[2] Hunter, D.R. & Burke, E.F. (1994). Predicting Aircraft Pilot Training Success: A Meta-Analysis of Published Research. International Journal of Aviation Psychology, 4(4), 297–313.

[3] Griffin, G.R. & Koonce, J.M. (1996). Review of psychomotor skills in pilot selection research of the U.S. military services. International Journal of Aviation Psychology, 6(2), 125–147.

[4] Carretta, T.R. (2011). Pilot Candidate Selection Method: Still an Effective Predictor of US Air Force Pilot Training Performance. Aviation Psychology and Applied Human Factors, 1(1), 3–8.

[5] Burke, E., Hobson, C. & Linsky, C. (1997). Large sample validations of three general predictors of pilot training success. International Journal of Aviation Psychology, 7(3), 225–234.

[6] DuBois, P.H. (1947). The Classification Program. Army Air Forces Aviation Psychology Program Research Reports, Report No. 2. Washington, DC.

[7] Damos, D.L. (Ed.) (2011). Selection in Aviation: A European Association for Aviation Psychology Report. Ashgate Publishing.

[8] Martinussen, M. & Torjussen, T. (1998). Pilot selection in the Norwegian Air Force: A validation and meta-analysis of the test battery. International Journal of Aviation Psychology, 8(1), 33–45.

[9] Drollinger, J. et al. (2015). As cited in: High-stakes psychomotor ability assessment: A military selection case study of practice effects in airplane tracking tasks. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications (2025). Springer Nature.

[10] Video Game Skills across Diverse Genres and Cognitive Functioning in Early Adulthood: Verbal and Visuospatial Short-Term and Working Memory, Hand–Eye Coordination, and Empathy. (2024). PMC/NIH.

[11] Adams, B.J. et al. (2012). Video gaming enhances psychomotor skills but not visuospatial and perceptual abilities in surgical trainees. Journal of Surgical Education, 69(6), 714–717.

[12] Prokopczyk, A. & Wochyński, Z. (2022). Influence of a special training process on the psychomotor skills of cadet pilots – Pilot study. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1019495.

[13] Federal Aviation Administration (2019). Best Practices in Pilot Selection. Report No. AM-19-06. FAA Civil Aerospace Medical Institute.

With a section dedicated to Motor Skills, our one-of-a-kind software represents the ultimate way for you to get prepared.

By leveraging our cutting-edge software, including those unique features and extensive guidance not offered elsewhere, you can immerse yourself in realistic simulations, master those competencies assessed, and familiarise yourself with the methods and mechanisms of assessment.

Our software is backed by our meticulous attention to detail and deep expertise as experienced commercial pilots, empowering pilot applicants to approach their assessments with confidence and helping to propel them to supersonic levels of success.

Start using our incredible preparation software immediately on PC, Mac, iOS and Android by purchasing a subscription:

Buy Preparation SoftwareWith increasing prevalence and awareness of computerised pilot aptitude testing in pilot assessments, it's never been more important to ensure that you can fly past the competition. This is made easy with features unique to our software:

Discover the key advantages of using our cutting-edge software:

How can I prepare for my Motor Skills pilot assessment?

The best way to prepare for your Motor Skills pilot assessment is with our latest industry-leading software, developed over 5 years by experienced airline pilots. With realistic exam simulations, personalised Preparation Strategies which guide you through your preparation, immersive Explainer Videos, customisable Training Modes that manipulate your simulation environments, comprehensive Instruction and Guidance, and extensive performance feedback which incorporates unique features such as Predictive Scoring, a Strength & Weakness Map and Colour Coding, our unique software will help you to accelerate improvement of your problem areas and fly through each part of the Motor Skills assessment. The software runs in a web browser, is compatible with laptop, desktop, tablet and smartphone, and is complimented with extensive support, provided from 9AM to 9PM GMT. To purchase a subscription to our software and start preparing for your Motor Skills pilot assessment, click here!

What is the pass mark for the Motor Skills pilot assessment?

Many pilot aptitude tests do not have a fixed threshold (or pass mark), but rather indicate the pilot candidate's overall performance and suitability using a variety of different methods - many of which are emulated within our software. Rather than worrying about a specific pass mark, the better approach is to focus on comprehensive preparation that maximizes your chances of success within each part of the Motor Skills pilot assessment. Our industry-leading pilot preparation software provides that comprehensive preparation, helping you to develop the essential sklls, familiarity with assessment and confidence needed to perform at your best. If you have any questions about the Motor Skills pilot assessment, please contact us.

How often is your Motor Skills assessment preparation software updated?

Our pilot assessment preparation software is continuously updated, with daily improvements based on feedback from hundreds of monthly users. Developed by experienced airline pilots, the simulations provided within our unique software faithfully reflect the Motor Skills pilot assessment, ensuring that you have the most current and comprehensive preparation. To see the recent updates to our preparation software, please visit our Updates page.

What support is available with your Motor Skills assessment preparation software?

With our own industry experiences, we understand the pressures and stresses that come with preparing for pilot assessments. When you use our software to prepare for your Motor Skills pilot assessment, you'll have access to exceptional support and guidance from our team of experienced airline pilots, provided between 9AM and 9PM GMT. This support sets us apart, helping you to develop the skills, knowledge, and confidence needed to approach your assessment feeling completely ready to demonstrate your true potential and fly past the competition at every stage of the Motor Skills pilot assessment.

How quickly can I prepare for my Motor Skills pilot assessment with this software?

If you'd like to start preparing for the Motor Skills assessment, you may start using our software within as little as a few minutes. We offer access to our preparation software for 7 days, 1 month or 3 months, and provide the opportunity to purchase additional time. This ensures you can work through the comprehensive simulations, and benefit from our guidance at your own pace, with support available whenever you need it. To get started, choose a subscription duration to our preparation software, create an account and complete your purchase - then, login and begin your preparation. The entire process typically takes between 2-3 minutes, with secure payment by credit or debit card securely processed with Stripe or PayPal.

Feature-packed and one-of-a kind preparation software for your assessment.

Regularly updated, realistic and infinite simulations of aptitude tests.

Instant activation, fast support and uniquely in-depth guidance.